Ira L. Black/Corbis via Getty Images

- Advocates argue traffic stops target drivers of color and call for them to be banned

- Most police killings originate from low-level incidents like mental health crises and traffic stops.

- If passed, the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act would eliminate "qualified immunity" for police.

- Visit Insider's homepage for more stories.

South Carolina Senator Tim Scott argued "America is not a racist country" in his remarks following President Joe Biden's address to a joint Congress Wednesday.

"It's wrong to try to use our painful past to dishonestly shut down debates in the present," he said in the official Republican response. But the lone Black, Republican senator went on to detail his own experiences with discrimination, recalling being called an "Uncle Tom and the 'N'-word."

In the past, the senator has recalled how he had been stopped by South Carolina police seven times in one year, linking the incidents to his state's record of racial disparities in traffic stops.

"I have felt the anger, the frustration, the sadness and the humiliation that comes with feeling like you're being targeted for nothing more than just being yourself," Scott said at the time.

And experts note there's overwhelming evidence supporting that, on average, police nationwide are more likely to stop Black and brown drivers than white drivers – including the senator's home state of South Carolina, where police are three times more likely to stop Hispanic drivers than their white counterparts.

Advocates are calling for reform as they say these interactions often stem from mundane, non-moving violations that target drivers at color.

Researchers tell Insider Black and brown drivers are stopped by police more often than white drivers

AP Photo/John Minchillo

Many police interactions stem from what law enforcement officials call "pretext" stops, or violations for non-moving infractions like vehicle tags and registration. Some state laws even use bans on license plate frames or air fresheners hanging in review mirrors to stop, ticket, and search motorists.

"In almost every jurisdiction we looked, we found that Black and Hispanic drivers are searched more often than white drivers," Cheryl Phillips, a journalist and cofounder of the Open Policing project at Stanford, told Insider.

Phillips said although police search Black and Hispanic drivers more often, they're less likely to be found with contraband than white drivers. But according to Open Policing's research, police in general apply a lower bar of suspicion to Black and Hispanic drivers.

While, the number of pre-text stops that lead to fatal police encounters isn't known, some experts warn the disparity among drivers of color puts their communities at disproportionate risk.

According to a 2020 report from Mapping Police Violence, police killed 121 people nationwide during traffic stops last year. A disproportionate number of the victims were Black.

Samuel Sinyangwe, the founder of Campaign Zero and Mapping Police Violence, told Insider most police killings last year began with low-level incidents such as traffic stops, but also incidents like mental health emergencies - interactions he said don't require a response by "someone with a gun."

"We've been here so many times before," Sinyangwe said. "I just hope that this time we can have a serious conversation that will lead to action."

Mapping Police Violence data showed Black people were three times more likely than white people to be killed by police during all low-level incidents, and four times more likely to be killed by police during traffic stops specifically.

Law enforcement experts, however, have argued that traffic stops are equally, if not more dangerous, for police.

According to a report from the National Law Enforcement Officers Memorial Fund, a nonprofit group that tracks officer fatalities, nearly 45 police officers were killed in traffic-related incidents in 2020. As a result, officers are trained to expect high-risk situations.

However, the probability of a police officer dying in a traffic stop is less than 1 in 6.5 million. Still cities and states across the country are offering solutions.

Some police departments have outlawed traffic stops to combat profiling

In North Carolina, Black men are more than three times more likely to be pulled over for a traffic stop than white drivers. The problem had became so bad that the police in Fayetteville launched an initiative to combat it.

The police department there halted traffic stops for non-safety related violations and instead focused on unsafe drivers. While the number of overall traffic stops more than doubled in four years, the percentage of Black drivers plummeted to a fifth of its previous level. As a result, fatalities in Fayetteville dropped too.

But not every effort to reform traffic stops worked as well.

Police in Nashville, Tennessee and Los Angeles, California banned traffic stops for all non-moving violations, including broken tail lights and expired registration. Although the number of overall stops dropped in Nashville since the updated policy was introduced in 2018, Black drivers were still disproportionately targeted.

Phillips suggests police departments rethink their reasons for conducting traffic stops altogether, saying contrary to what many police officers believe, there's "no impact of traffic stops on serious crime."

Others go further, calling for armed police to be completely removed from all low-level infractions including traffic stops, but also nonviolent domestic disputes or mental health crises. Sinyangwe suggests that will drastically reduce the number of police killings.

Some cities have already taken that step. Eugene, Oregon's CAHOOTS program sends highly-trained care professionals instead of armed police to deal with mental health crises. Last June, Denver, Colorado piloted the STAR program, which does the same thing.

"This is a moment where people are looking for solutions," Sinyangwe said. "And we don't have to start from square one."

Legislators have proposed federal solutions including the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act

Melina Mara/Pool/AFP via Getty Images

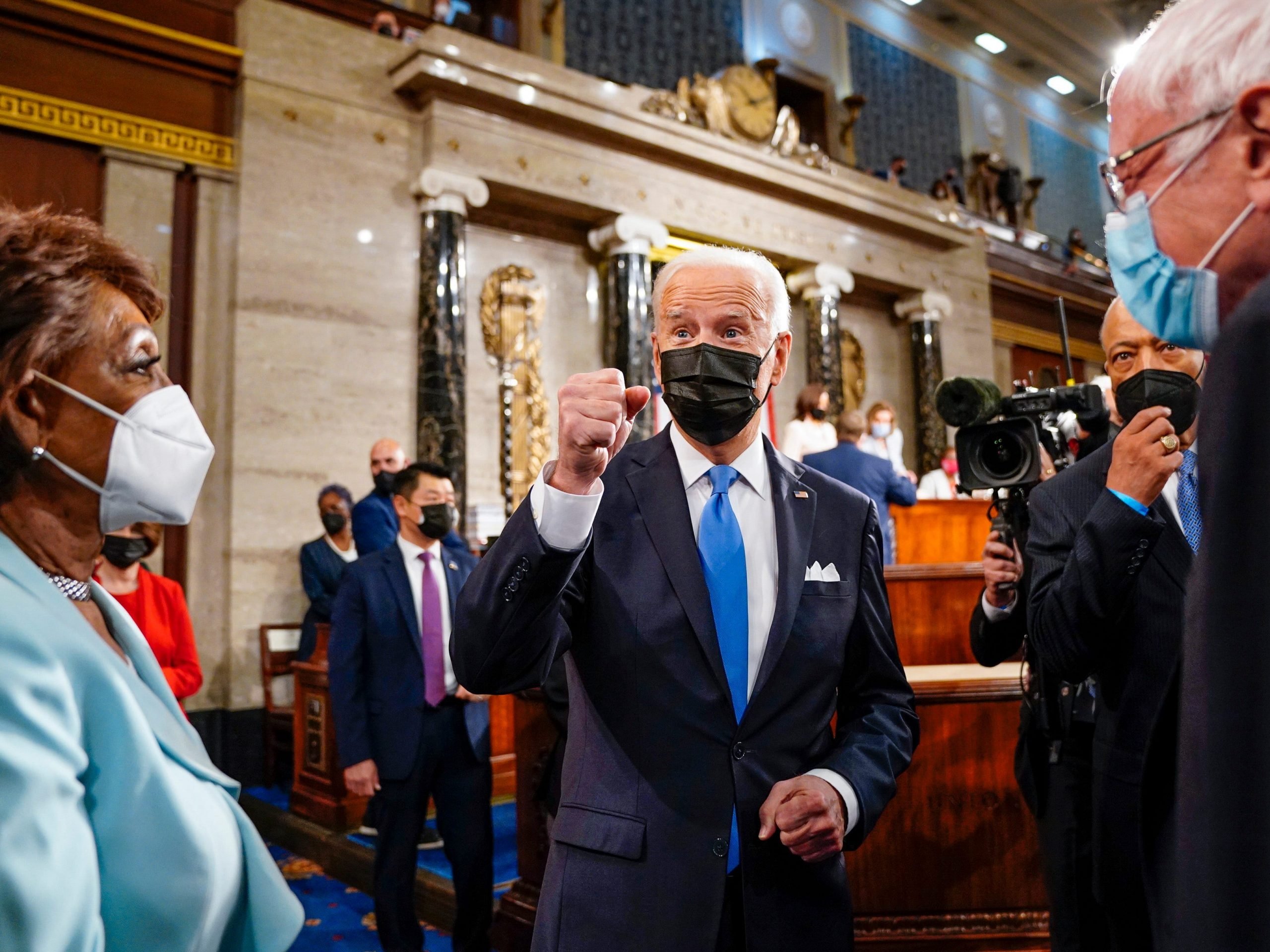

In his address Wednesday, President Joe Biden echoed the need for the nation to forge a new path on policing - calling for the US Senate to pass the George Floyd Justice in Policing Act.

It is named after the 46-year-old Minneapolis man who was killed following a May traffic stop last year after former police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for more than eight minutes. Nearly a year after a summer of worldwide racial justice protests, Chauvin was convicted of all charges related to the murder in April.

At the federal level, the bill would ban the use of neck restraints, ban no-knock warrants in drug cases, and eliminate "qualified immunity" for police officers - an element some advocates say shield from prosecution the officers who kill people during traffic stops.

Authored and led by Democrats Rep. Karen Bass of California and Sen. Cory Booker of New Jersey, the initiative is a bipartisan effort thanks in part to South Carolina Senator Tim Scott.

But while simultaneously relaying personal efforts to reform American police forces and dismissing the institutional racism that warranted it, Scott lamented "building an even bigger police reform proposal" in response to the deaths of Floyd and Walter Scott following a traffic stop in his home state in 2015.

"But my Democratic colleagues blocked it," he said. "My friends across the aisle seemed to want the issue more than they wanted a solution."

"But I'm still working," he said. "I'm hopeful that this will be different."

Reform mostly rests with Democrats who, although they hold a tie-breaking vote, face obstacles in passing the legislation. President Biden called the Senate to move forward with passing the bill before the one-year anniversary of Floyd's death, and for Americans "to come together to heal the soul of this nation."

"We've all seen the knee of injustice on the neck of Black America," Biden said, invoking Floyd. "Now is our opportunity to make some real progress."

Dit artikel is oorspronkelijk verschenen op z24.nl